Different Strokes for Different Folks: Taxonomies Around the World

“Tot controversiae inter Auctores! Tot mala nomina! Tanta confusio!”

“So many controversies among authors! So many bad names! So much confusion!”

This is Carl Linnaeus in 1737, frustrated by plant names that didn’t suit him. Thus, he set about naming plants in a reference language (Latin) and categorizing them by how similar or different they were from one another. This method, along with later insights from Charles Darwin, forms the basis of scientific taxonomy today.

You’re likely familiar with this story. But what prompted these organizational problems in the first place? In short, Linnaeus was helping solve the problems of empires.

European colonial projects were bringing back unfamiliar plants from occupied lands. They were moving people and plants farther and faster than Europeans had ever experienced before, and they were working with many languages. How were people to grow, ship, study and trade plants without a common reference? Linnaeus wanted to help Europeans, as he saw it, order the world. He even used his classification system to justify enslavement and conquering by ranking other skin tones as lesser types of human beings.

"Genera Plantarum" by Carl Linnaeus, publication date 1737. Courtesy of Helen Fowler Library rare book collection.

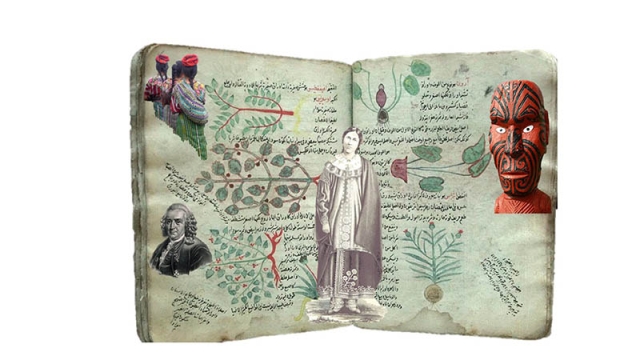

Linnaeus is not the first, nor the last, to try and organize plants. Let’s take a moment to step back and examine other types of taxonomies from around the world.

Linnaeus is often credited with popularizing the use of a common language for plants, but the Muslim empires in the 800s to 1200s beat him to it. Scholars across the Muslim world communicated across the territories from modern day Spain to Persia. This written common language for plants helped people experiment with crops in different climate regions and grow diverse collections in botanic gardens.

Mayan speaking peoples still use the classification system embedded in their language. Cultivating milpas and tending to forest plants is central in Mayan culture. The detailed organization of plants in the languages exemplifies this. The Mayan classification goes from general (like the word wamal – meaning plants exhibiting net veined leaves and herbaceous to inflorescent stems) to specific (like sc’ul wamal, a type of amaranth). This pattern developed before the 1500s and is very similar to the genus and species of Linnaeus.

Naming can also tell us about ecological relationships. For example, the Maori names for honeyeater birds include information about what the birds eat in different seasons. The Iroquois creation story puts humans in a taxonomy as younger relatives of other animals.

Cultures the world over have organized knowledge about the world of plants. Image: Anthony Meluso

Today’s organizing method is not set in stone either. Some mycologists want to abandon the Linnean system for fungal classification. They argue that the fungal specimens don’t fit neatly into species categories. Instead, they propose tagging specimens with digital codes while they develop a new way to organize this extremely diverse field.

If you’d like to learn more about this topic, visit the Helen Fowler Library located on the first floor of the Freyer – Newman Center for Science, Art and Education. The Linnean Society of London holds the botanical, zoological and library collections of Carl Linnaeus. The Center for Plants and Culture uses plants to discuss history, economics and labor, arts and culture and are a POC-run organization highlighting Black, Brown, Indigenous and rural peoples. (See: Science, Racism, and Linnaeus)

Add new comment