How Did Soviet Scientists Lead the Way for Conservation?

The most well-known seed bank in the world is likely the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, which was built into a mountainside on an island off the coast of Norway in the early 2000s. However, the origin of the modern seed bank begins almost 100 years earlier in what was then the Soviet Union.

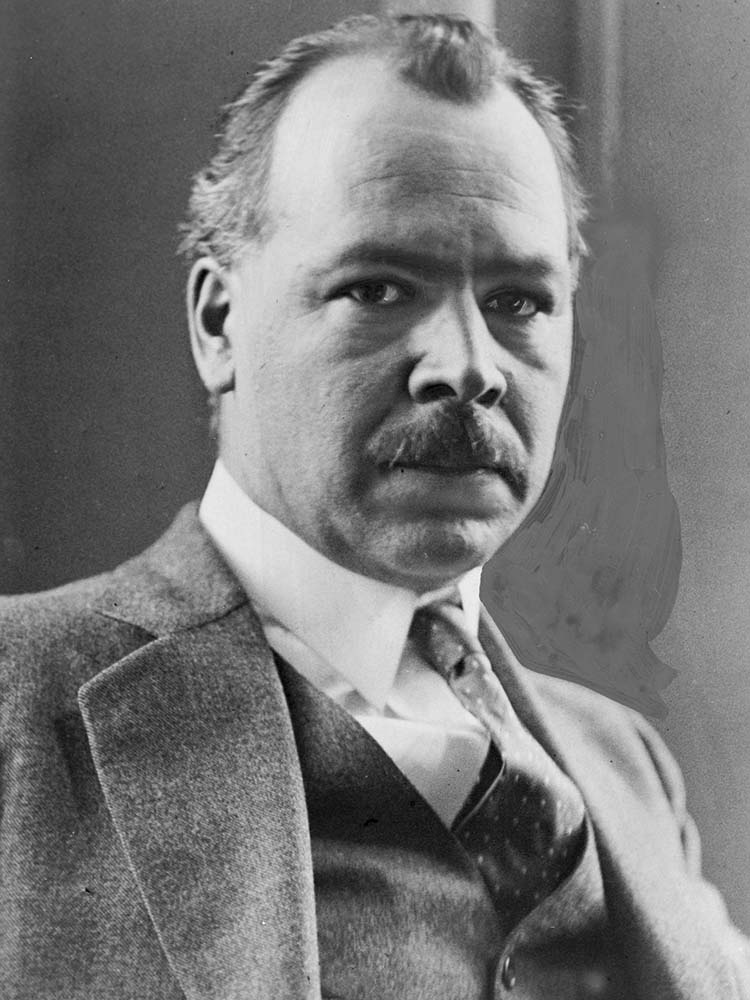

Nikolai Vavilov was a Russian botanist and geneticist in the 1920s – a period in which many people in eastern Europe were dying of starvation. Vavilov was interested in studying the origin of plant cultivation and crop diversity around the world in the hopes that he could find a solution to fight off crop failures. During his expeditions, he and his team collected hundreds of thousands seeds from 64 countries and brought them back to his home base in Leningrad, creating what was then the largest seed bank in the world.

The seed collections became a target in the Siege of Leningrad during World War II. For over two years, a group of scientists preserved and protected the seed collections in the basement of a building as they starved and fell victim to disease. In total, 12 of the scientists died of starvation while protecting the seeds, but the seeds survived. Svalbard is a direct descendent of the Leningrad seed bank and the scientists who collected and protected those seeds.

Until somewhat recently, most of the research in the world's seed banks had been primarily focused on seed collections and storage longevity of crop species. Alternatively, collections of rare species too often went into frozen storage with little data collected on the loss of viability of those collections during storage. But a few decades ago, scientists began strategically thinking about using seed banks to conserve rare native plant species in case of extinction or population loss.

The Gardens has been collecting seeds of rare native Colorado species since the late 1980s, when we became one of the first partnering institutions with the Center for Plant Conservation (CPC). Over the past 30 years, partnering institutions with CPC have been making seed collections of rare species across the United States and preserving those seeds in frozen storage. An Institute of Museum and Library Services grant was recently awarded to CPC to study ageing and longevity in wild rare plant species using biochemical indicators. To implement this method, seed collections that have been stored for over 15 years are compared to fresh seed collections from the same source location in the wild.

Over the next couple of years, I will make seed collections of five species that will be used in this study for which we have collections from over 15 years ago. This summer I made seed collections from two of the species, Aletes humilis and Phacelia formosula, and scouted for a third, Eutrema penlandii. Next year I will scout for the remaining two, Astragalus linifolius and Physaria obcordata. This new method of seed testing will help us to better conserve some of our most vulnerable native Colorado plants.

Gallery

Comments

Great Alex. Very…

Great Alex. Very interesting. Good job

Thank you

Thank you for the noble deeds and preservation of species and history! I wonder, how do you keep track of all these seeds. Is there an internal database, and an alarm/email notification if some of these seeds start to expire? It would be cool if it could be a more communal effort, and/or if more people knew how to recognize rare native species...

Hello, Thank you for your…

Hello,

Thank you for your comment and questions! We have an internal database to keep track of all of our seed accessions. Unfortunately there is no alarm/notification for when seeds start to expire (that would make things so much easier!) - we test viability in storage every few years to understand when seeds may start to lose viability. Some species can survive in storage for hundreds of years!

Add new comment