Representation in Botany and Horticulture: Part 5

The Gardens’ mission is to connect people with plants. The actions we take in pursuit of that mission are guided by our core values, one of which remains especially relevant today: diversity. We have an incredible and obvious diversity among our plant collections, but we also strive for a diversity in the people we are connecting with those plants.

Many items in the Helen Fowler Library sit at the intersection of people and plants, as a lot of our books can give us more than just the botanical information found within their pages; they retain cultural and historical associations with their authors, printers and publishers. We have books from all over the world – representing almost 30 different languages – in both our circulating and historical collections, and some of the stories we uncover when we look more closely at them are fascinating.

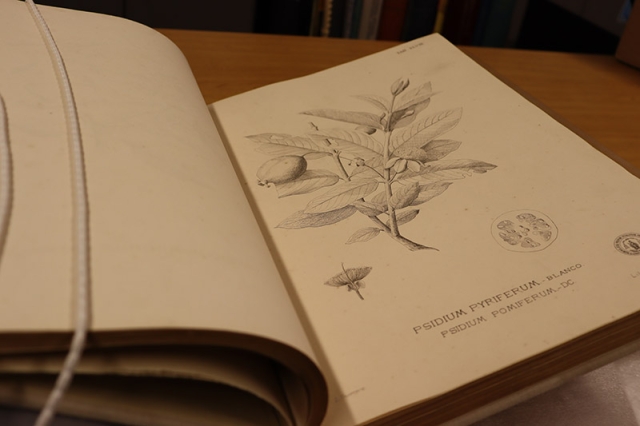

Take, for instance, our late 19th century copy of “Flora de Filipinas” – the work as a whole is made up of four text installments composed in Manila and two volumes of plates printed in Barcelona, all completed less than 20 years before the Philippines declared its independence from Spain. All the text is in both Latin and Spanish.

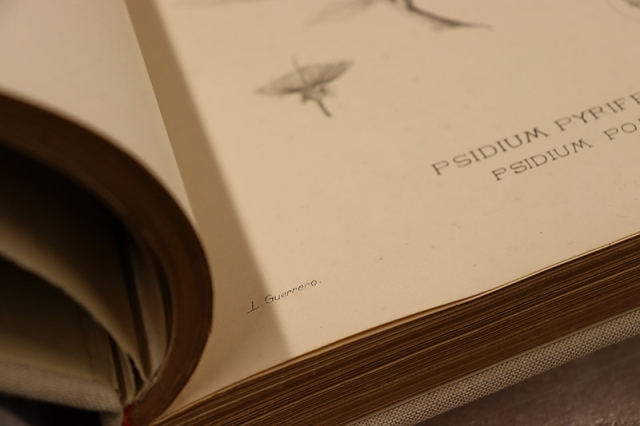

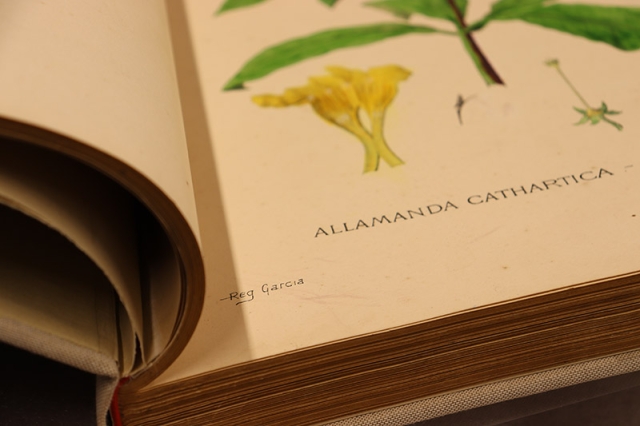

The chief illustrator of “Flora de Filipinas”, Regino García y Baza (1840-1916), was a Spanish mestizo artist and botanist. García headed a team of 12 Filipino and five Spanish artists, all of whom were born in the Philippines or had been living and working there for a while prior to the start of the project. They were all trained in the styles of Don Agustín Sáez y Glanadell and Don Lorenzo Rocha é Icaza, a very precise and academic training that ensured accurate depictions of the plants.

Those working on “Flora de Filipinas” did so during an interesting time in Spanish and Filipino history. The work was published in fascicles between 1877 and 1883. In 1872, there had been a small Filipino revolt against Spanish rule. In 1880 one of the artists, Lorenzo Guerrero y Leogardo (1835-1904), received an award from Spain for his art but refused to wear Western clothes and instead sported the Filipino barong tagalog as a show of nationalism for the pinning ceremony.

The chief illustrator, García, was one of two artists working on “Flora de Filipinas” later appointed to the Malolos Congress that ratified the Proclamation of Philippine Independence in 1898. Much of García’s work was lost when the United States bombed Manila during World War II but around 100 plates of his work can still be found in this book.

Explore more!

A copy of this work in the Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid has been digitized and is available online for anyone to view. While the Helen Fowler Library’s copy has black and white line drawings (with some hand-coloring added later), Madrid’s digitized version is one of the 500 copies that was issued in full color. Visit links in the library’s online catalog to decide which volume you’ll be exploring first!

Add new comment