Studying Fungal Associates of Two Native Wildflowers

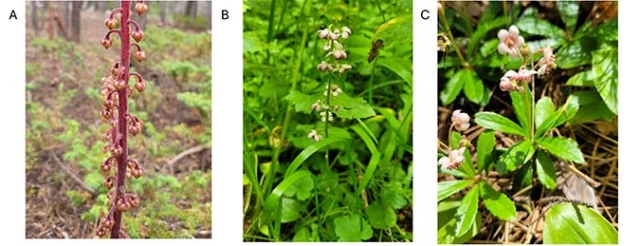

If you’ve been on a hike and seen a pinedrop, you might have thought, “Hey, why isn’t that green? Isn’t it a plant?” Well, it is! But it doesn’t do the one thing that makes plants so unique – it cannot photosynthesize. Pinedrops (Pterospora andromedea) fully rely on fungi for their nutrition.

Pinedrops are an extreme example of mycoheterotrophy, the use of fungi as nutrition. (Myco = fungus, heterotrophy = can’t make its own food, must have a food source.) While these full mycoheterotrophs are wacky and charismatic, they’re not the only plants using fungi as a carbon (food) source.

Partially mycoheterotrophic plants are green and photosynthetic, but also supplement their carbon using fungi. Another way they differ is that fully mycoheterotrophic plants associate with only a few species of fungi while partially mycoheterotropic plants typically can associate with a variety of fungal species.

Two partially mycoheterotrophic plants that grow in Colorado are bog wintergreen (Pyrola asarifolia) and pipsissewa (Chimaphila umbellata). They are green, herbaceous, rhizomatous perennials that are closely related members of the Pyroloideae subfamily within the Ericaceae family. Both plants require fungi to germinate, however bog wintergreen continues to utilize fungi through adulthood while pipsissewa does not (though it still associates with fungi, it does not receive carbon from them).

A) Pinedrops (Pterospora andromedea) at the Mountain Research Station near Niwot. Pinedrops have no chlorophyll and can’t photosynthesize, requiring a fungal partner for carbon. B) Bog wintergreen (Pyrola asarifolia), a partial mycoheterotroph as an adult, supplements its carbon using fungi. C) Pipsissewa (Chimaphila umbellata), closely related to bog wintergreen, requires fungi for germination, but does not utilize fungi as a carbon source as an adult.

I wanted to know which fungi these plants associate with as adults. Both plants occupy a wide native range in North America, across different types of mixed forests. For my study, I chose three locations to collect them from: the North Woods of Minnesota, the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California and the Southern Rocky Mountains in Colorado.

This summer, I sampled these roots with the help of volunteers. We had to carefully excavate the rhizomes to find the thin, fragile rootlets. The above-ground plant was collected and brought back to the Kathryn Kalmbach Herbarium, while the rootlets were dried to preserve the DNA inside. Soil cores were also collected, to see which fungi were available in the environment. In the lab, I will extract DNA from soil and rootlets and then send the samples out for sequencing to identify the fungi. I’m excited to see which fungi these plants are associated with!

Top, left to right: Volunteer Taye Bright and Jessica Loeffler in California; pipsissewa sample

Bottom, left to right: Volunteer Bella Briganti, California; volunteer Jonny Tormoen, Minnesota; bog wintergreen sample

This article and photos were contributed by Jessica Loeffler, graduate student.

Add new comment