Leucophysalis grandiflora, what are you doing here?

In soil, there is a natural storage of seeds—known as the soil seed bank—even in urban areas. These soil seed banks can serve as a potential source of species diversity for plant communities, particularly in areas undergoing disturbance.

For my master’s thesis research, I am investigating the soil seed bank in a one-mile section of the High Line Canal that has undergone recent developments to become a green stormwater infrastructure (GSI). The increase in water expected from this GSI implementation will likely cause a disturbance to the plant community here.

Disturbance is a shifting of ecological conditions that may cause plant communities to change. Those changes might be ecologically beneficial, such as an improvement in community resilience with species that can handle the wetter conditions and do the work of GSI. On the other hand, the changes could lead to a degraded plant community that can’t handle the new conditions and doesn’t function as desired. The seed bank impacts what change could come, and by exploring its composition, I can try to anticipate what that change will look like.

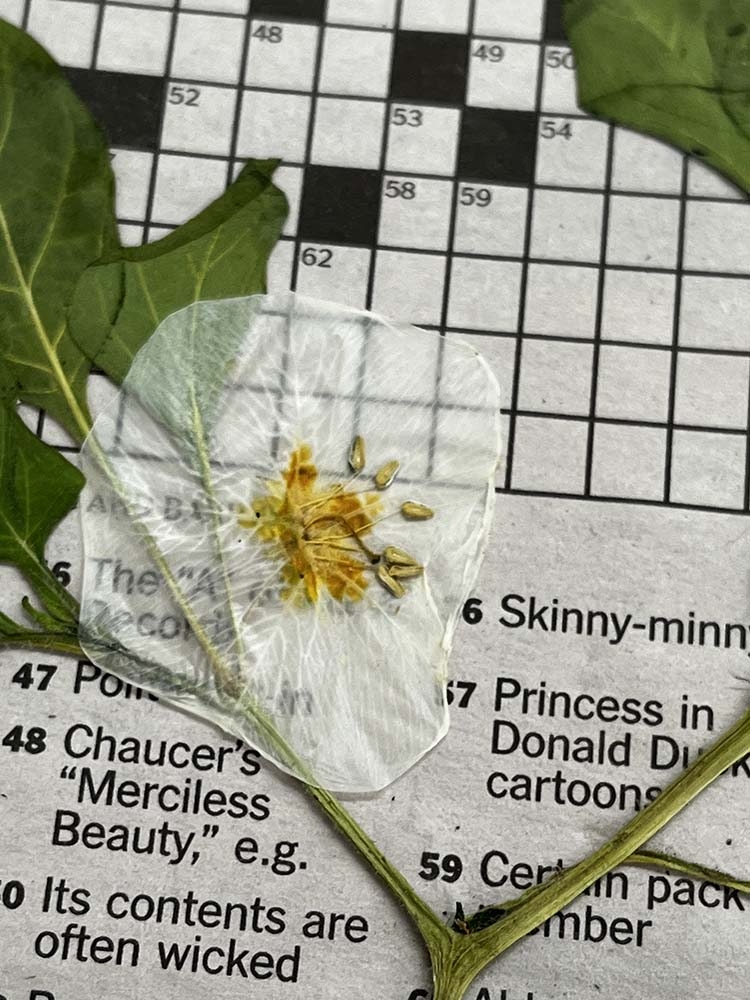

We bagged soil samples, and I attempted to identify the germinants that came up. While I was working on identifications, a mysterious beauty caught my eye. A single white flower with a fused corolla and bright yellow nectary guides popped up out of the greenhouse trays to say hello. The fused white corolla reminded me of a potato flower or a field bindweed. I brought the specimen to the Kathryn Kalmbach Herbarium and chatted with all the awesome plant experts we have on staff to no avail. I reached out to the horticultural staff in case this enigmatic germinant might be a garden escapee, unfamiliar to those of us who primarily focus on the wilder species. Eventually the email chain found its way to a Colorado Master Gardener who happened to recognize this beguiling mistress. “Check out Leucophysalis grandiflora!” she said.

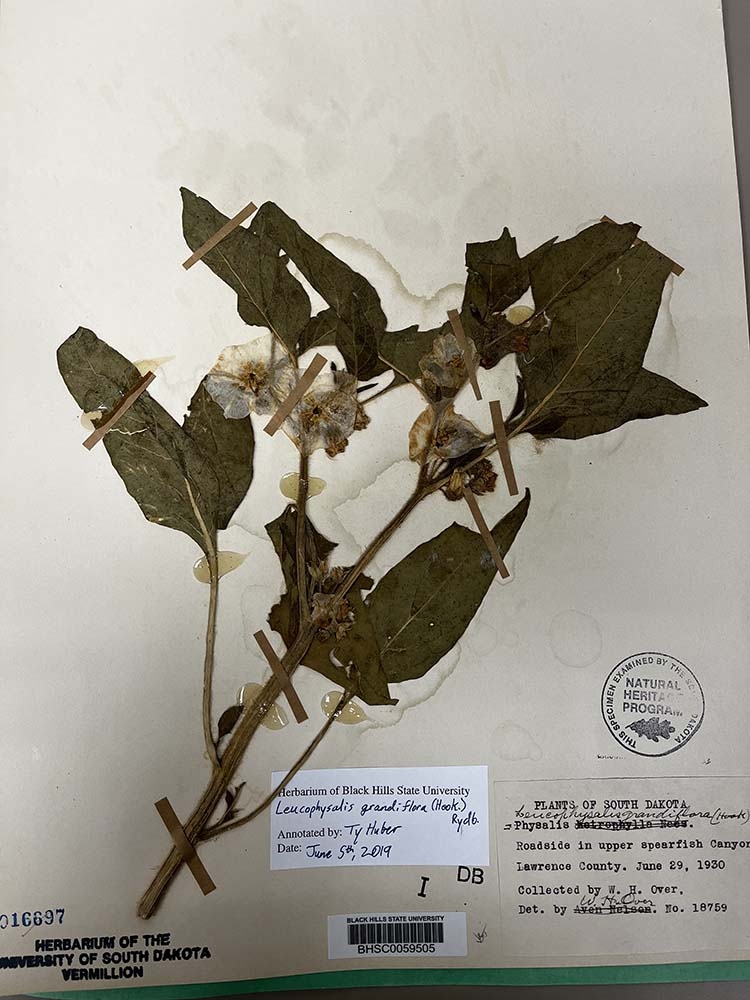

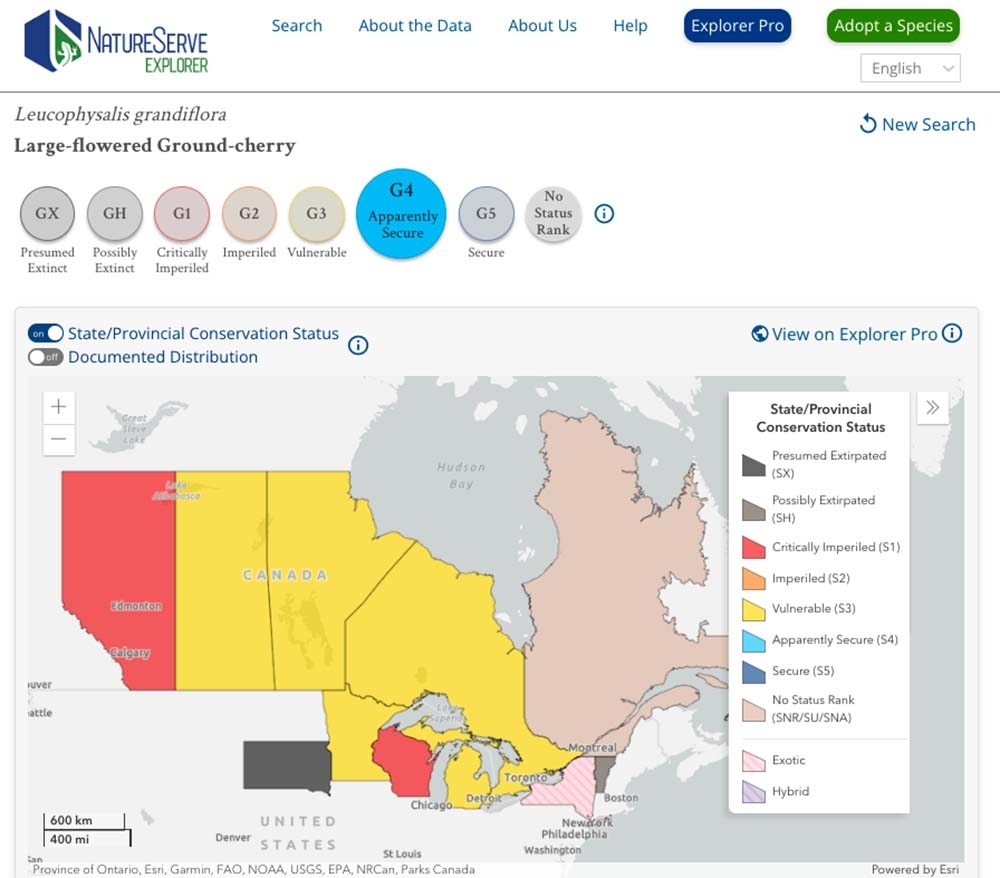

To confirm, I checked out-of-state keys and even went to the Black Hills State Herbarium in South Dakota, where they had a specimen, to make a comparison. But the identification only made things more curious as there is no known record of L. grandiflora in Colorado. The native range of this species is near the Great Lakes, and even then, it’s rare! The closest known populations on record were in South Dakota in the Black Hills. Since there are no records past the 1942 in South Dakota, it is likely extirpated from the state. Even her established range in Michigan, Wisconsin, and parts of Canada, appears to be shrinking.

What further deepens the mystery is the pattern of survival and reproduction (aka “life history”) for L. grandiflora is unusual—she prefers disturbed areas, such as an area with a recent burn or flooding. Following the disturbance, after the plant community begins to stabilize, she leaves. This ephemeral quality makes it challenging to know much about this species.

This identification and subsequent information raises questions: Why is this species here? Would she have germinated on her own, if not for the warm, wet greenhouse conditions? Are there more seeds in the soil along the Canal? Could there be an established, but undocumented, population of L. grandiflora in Colorado? Could a migrating bird have dispersed her berries from a great distance while visiting the Canal? How long was this seed in the seed bank? Is someone, somehow, using this pretty flower as a garden cultivar and she made a run for it?

Alas, without further information we can only guess. Until then, she can keep her secrets. For my study, this unique find sheds light on the possibilities that can be found in the soil seed bank. By exploring the potential change it harbors, we may find unlikely fellows.

This post was contributed by Graduate Student Alissa Iverson.

Gallery

Add new comment