Favorite Botanical Finds Along the High Line Canal

The verdict is in: Here are our research team’s favorite botanical finds along the High Line Canal!

If you’ve ever spent time on the High Line Canal Trail, you may be familiar with some of the common trees and shrubs. Maybe you’ve walked beneath the snowy arms of the cottonwood trees (Populus sp.), ridden your bike past a stand of American plums (Prunus americana) or marveled at the beautiful chokecherry blossoms (Prunus virginiana) while out for a run. And it’s no wonder; these larger species are hard to miss!

But good things come in small packages, too. More than 30 days of botanical fieldwork on the High Line Canal has revealed many interesting native species that are easily overshadowed by their taller neighbors. Here are five such treasures to search for on your next visit to the Canal Trail.

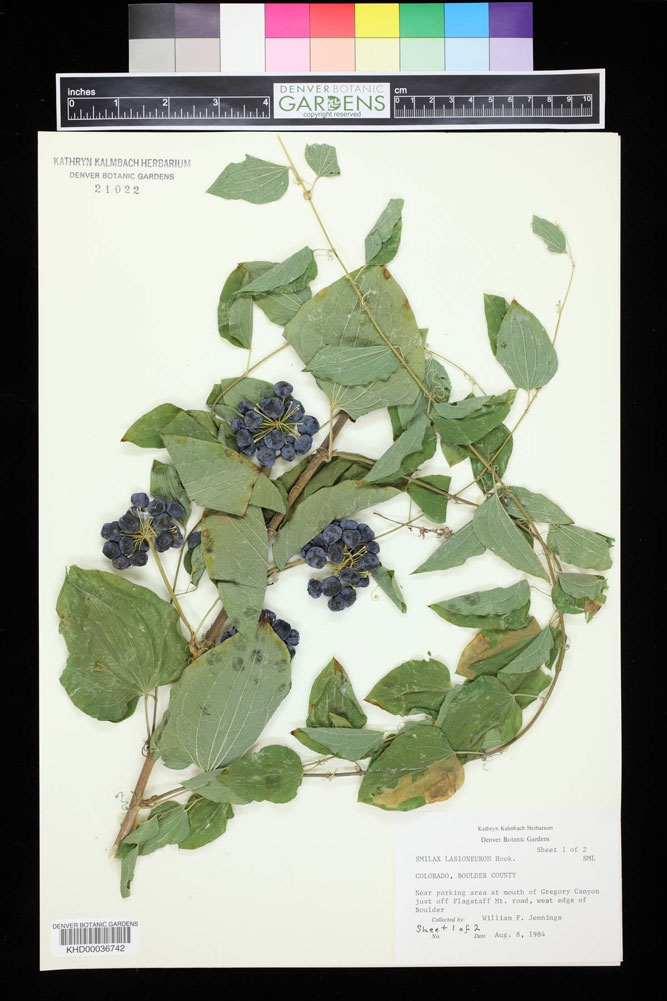

Smilax lasioneura (Blue Ridge carrionflower), Smilacaceae (catbrier family)

Distribution and habitat: The Blue Ridge carrionflower is distributed across the central plains as far west as Montana. In Colorado, it is found in only a few counties along the eastern foothills of the Front Range. Its habitat includes forests and shaded slopes as well as open areas such as old pastures. Our research team found it growing along the High Line Canal on a shady slope near Waterton Canyon.

Fun facts: As the name “carrionflower” suggests, the flowers smell like rotting flesh and attract flies, which act as pollinators. It is dioecious, which means the male and female flowers are found on two different plants (dioecious is derived from the Greek word “-oikos” which means home, and “di-“, which is Latin for two).

Etymology: Lasioneura is derived from “lasios”, which is Greek for hairy, and “neur”, which is Greek for nerve or vein. This name describes the hairy veins on the undersides of the leaves.

Ethnobotany: The Blue Ridge carrionflower provides food for wildlife and, in some regions, domestic stock. The seeds were occasionally used by Native Americans as decorative beads, and the woody roots were used to make a brown dye or carved into pipes.

Quick guide:

- Unarmed (lacking thorns) perennial vine that climbs using tendrils

- Large heart- or oval-shaped leaves that are slightly hairy on the underside

- Small green flowers in a round, golf ball-sized umbel (a cluster of flowers attached to the stem at the same point)

- Dark blue-black berries

Ipomoea leptophylla (bush morning glory), Convolvulaceae (morning glory family)

Distribution and habitat: Bush morning glory is native to the mixed-grass prairies of the Great Plains, and it is common in the Eastern Plains of Colorado. Our research team has found it in several places along the High Line Canal, from near Chatfield State Park in Littleton to Green Valley Ranch in northeast Denver.

Fun facts: Another common name is manroot because its roots grow deep into the dry prairie soil in search of water. The massive taproot can grow up to 10 feet long and 6-24 inches wide! This extensive root system is used to store water and nutrients, which help the bush morning glory survive drought and live for as long as 50 years.

Etymology: Ipomoea is Greek for "worm-like", referring to the viney, twining habit of many other Ipomoea species (but not this one). Leptophylla is derived from the Greek words “leptos”, meaning delicate or slender, and "phyllos", which means leaves.

Ethnobotany: Native Americans had several purposes for the large root. It was burned and the smoke was said to alleviate nervousness or bad dreams. It was also scraped and eaten raw as a gastrointestinal aid to relieve stomach problems or roasted and used as a starvation food source. This particular use is not surprising, as it is in the same genus as the sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas).

Quick guide:

- Bushy perennial that can grow 1-4 feet tall and up to 5 feet wide

- Narrow green leaves that tend to grow on the same side of a yellow-green stem

- Large, showy funnel-shaped pink-purple flowers

Sphaeralcea coccinea (scarlet globemallow), Malvaceae (mallow family)

Distribution and habitat: Scarlet globemallow is found in dry areas of the Intermountain West, the Great Basin, the Rocky Mountains and the Great Plains. It is extremely drought-tolerant and grows in desert, semi-desert and prairie habitats, as well as roadsides and disturbed areas. Although our research team has found it in several places along the High Line Canal Trail, it is not abundant, so you’ll have to look carefully to find this lovely native flower!

Fun facts: The flowers and leaves of scarlet globemallow provide food for many wild animals, including pronghorn antelope, deer, bighorn sheep, bison, prairie dogs and jack rabbits, as well as domestic sheep. Livestock will also eat the plants when grasses are dormant.

Etymology: Sphaeralcea is derived from the Greek "sphaira", which means globe (referring to the shape of the fruits) and “alcea”, which refers to the mallow family. Coccinea is Latin for "scarlet".

Ethnobotany: There are several uses for scarlet globemallow, including as a tonic to improve appetite. The chewed roots and dried leaves can also be applied to sores as a disinfectant.

Quick guide:

- Small perennial wildflower that only grows 4-16 inches tall

- Lobed leaves that are densely covered with stellate (starburst) hairs, giving a grayish-green frosted appearance

- Deep orange to orange-pink flowers with a yellow column in the center

Argemone polyanthemos (crested prickly-poppy), Papaveraceae (poppy family)

Distribution and habitat: Although the crested prickly-poppy’s native range extends from the eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains to the central and western Great Plains, it has been introduced in several adjacent regions, including west of the Rockies. It grows in sandy or gravelly soils in prairies, foothills, and mesas, as well as disturbed areas like roadsides or fields. During the summer, the brilliant white flowers are easy to spot! Look on the side of the High Line Canal Trail opposite the canal in sandy areas.

Fun facts: All Argemone species have a milky sap that ranges in color from white to reddish-orange; the sap of the crested prickly-poppy is bright yellow. Plants often use sap as a deterrent to avoid being eaten.

Etymology: Argemone stems from the Greek word "argemos", a white spot or cataract on the eye, which the plant was used to treat. "Poly" means "many", and "anthemos” refers to the pollen-containing structures, called anthers.

Ethnobotany: Although all parts of this plant are poisonous, it was once used to treat cataracts.

Quick guide:

- Deep-rooted annual or biennial that grows 1-3 feet tall

- Pale blue-green leaves with spines along the veins on the undersides

- Showy white poppy-looking flowers with yellow centers

- Broken stems ooze a bright yellow sap

Abronia fragrans (snowball sand verbena), Nyctaginaceae (four o’clock family)

Distribution and habitat: Snowball sand verbena is distributed in the shortgrass prairie of the western Great Plains and at lower elevations of the Southern Rocky Mountains as far west as Utah. It grows in desert, grassland, pinyon-juniper and ponderosa pine communities. Our research team has found it in multiple places along the High Line Canal Trail, and it is abundant in sandy areas near Chatfield State Park.

Fun facts: Like many other members of the four o’clock family, the flowers of the snowball sand verbena open in the evening and close again in the morning.

Etymology: Abronia is from the Greek word "abros", which means delicate. Fragrans is Latin for "fragrant”, referring to the sweet-smelling flowers.

Ethnobotany: Snowball sand verbena has been used medicinally and for food. Native Americans of the Southwest use the plant to treat insect bites, sores, and stomachaches, and the roots can be ground up and eaten in a mixture with corn flour.

Quick guide:

- Sweet-smelling white flowers that form a spherical umbel (a round cluster of flowers attached to the same point on the stem)

- Stems that sprawl on the ground before growing upright

- Sticky, oval-shaped leaves

This blog post was written by Audrey Dignan, seasonal botanist in the Research & Conservation Department.

Gallery

Add new comment