The Challenges of Germinating Rare Alpine Species

If you think about hiking in the mountains of Colorado during different seasons of the year, you might recall seeing plants at different stages of their life. After the snow melts in the spring, greenery begins to emerge from the cold, solid ground. By June or July, many of the alpine plants are in full flower. And by August or September, you might notice that those flowers have turned to dried-out fruit capsules filled with hundreds to thousands of tiny seeds.

Those seeds are then released and fall to the ground, only to experience the harsh conditions of mountain life only a few weeks later. The tiny seeds get buried in multiple feet of snow for a few months before their life as a plant can begin in the spring. This period of snow burial and cold conditions has led seeds to evolve a type of dormancy called physiological dormancy, meaning that they need a period of cold before they can germinate in the spring. If you think about it, this makes a lot of sense, because if the seeds were to germinate in the fall immediately after they are dispersed, that tiny seedling would quickly die from the ensuing cold temperatures and snow.

We can use information such as habitat conditions of a plant to predict what requirements are needed for germination. For many plant species, particularly rare alpine species, there is little to no information about the requirements needed for germination.

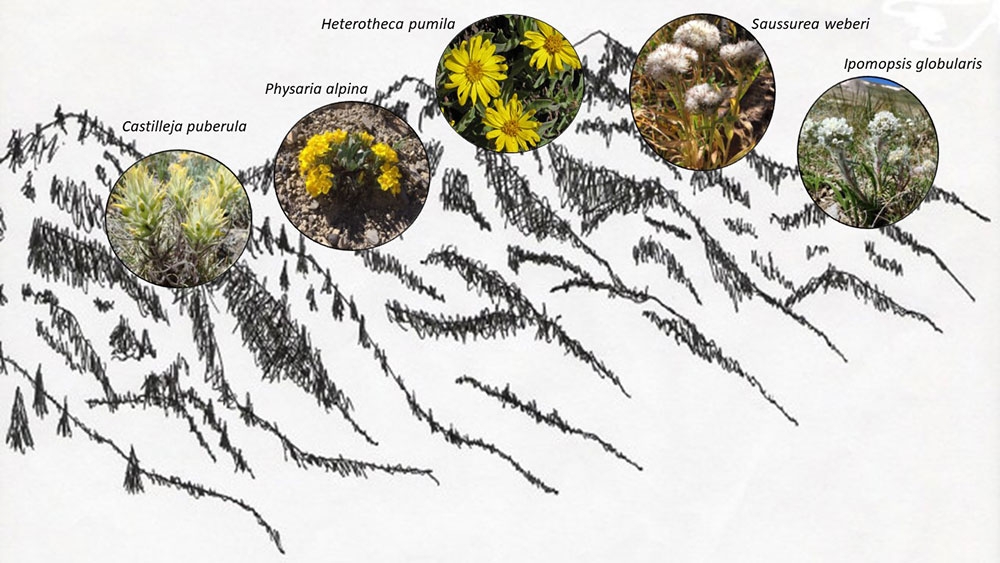

For example, four rare alpine species from which seed was collected in 2018 – Castilleja puberula, Ipomopsis globularis, Physaria alpina and Saussurea weberi – have practically no information on what they require for germination. As such, I had to think about the environmental conditions of the habitats from where these seeds were sourced, as well as the likely dormancy classification of these species. The latter of which was done by looking at closely-related common species, as species within the same genus or family will often have the same type of dormancy.

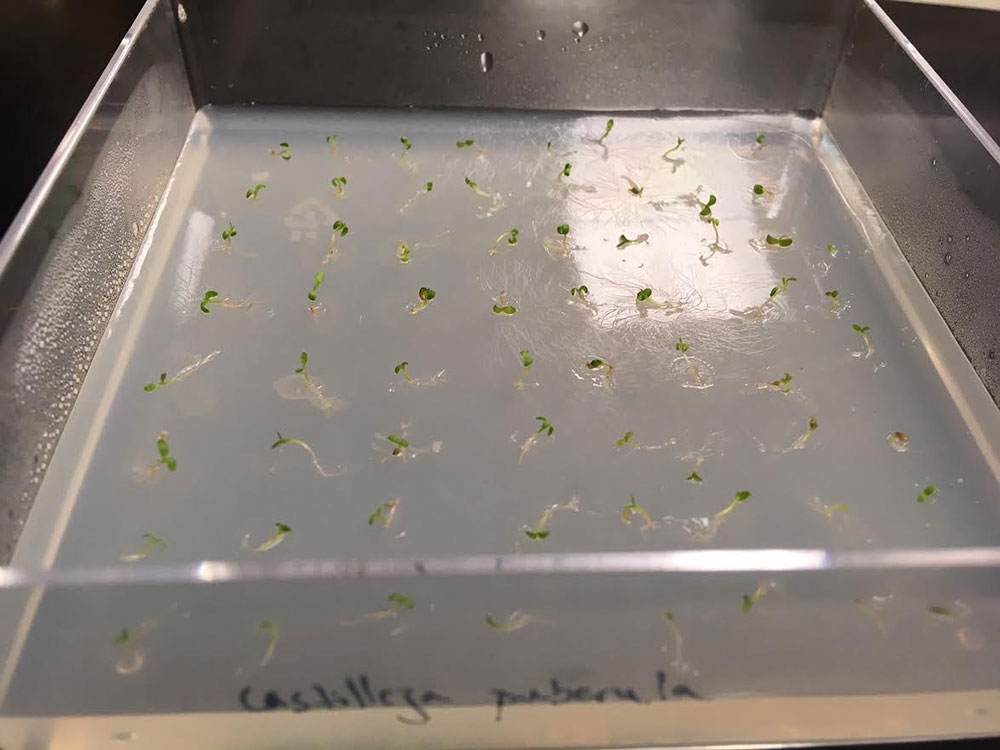

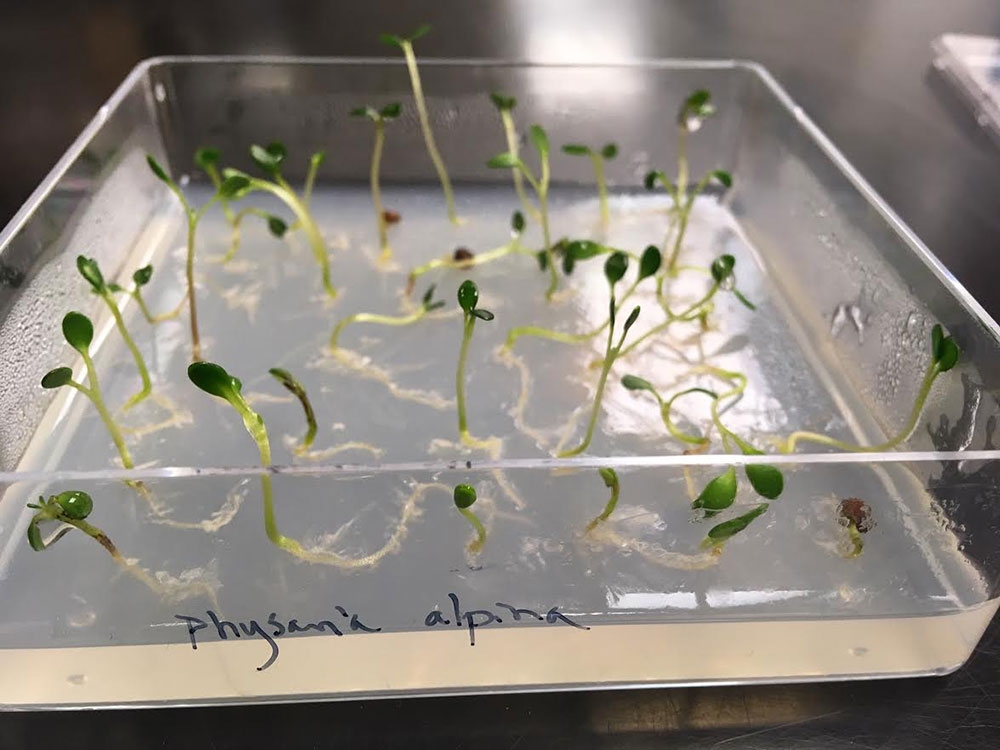

Based on the knowledge of the environmental conditions of the source habitat, we can infer that freshly collected seeds likely need a period of cold in the lab setting before they will germinate. I subjected seeds to different lengths of cold stratification in a refrigerator at about 35°F, ranging from two weeks to 12 weeks, before placing them in an incubator at two different temperature regimes to mimic spring and summer conditions in the alpine environment. The experiment is still running, but from preliminary results it appears the species mostly prefer the warmer summer conditions.

With this baseline germination information, we can proceed with other questions and experiments that will tell us more about these little-studied species. As part of an Institute of Museum and Library Services grant, the Gardens is collaborating with other public gardens around the United States to research “exceptional” plant species, or those that cannot be stored in traditional ex situ seed bank conditions for conservation purposes. Studies in Italy and Australia have shown that alpine species in those countries are short-lived in seed banks compared to low elevation species.

The Research & Conservation Department at the Gardens will conduct similar ageing experiments to determine if these patterns are also present in North American alpine species. However, before these experiments can begin, we need to understand the basic germination requirements of the species to understand how viability and germination may be affected over time during long-term frozen storage in a seed bank.

Gallery

Add new comment